Superstition and witchcraft have always been part of human societies throughout history. In early civilizations, humans turned to magic and superstition in their desire to control natural elements, diseases, and unknown forces. Women, in particular, were often associated with witchcraft and, on many occasions, were punished for being labeled as witches. This article explores the fascinating journey of witches and superstitions from ancient times to Pinky Pirni.

The Early Era: The Beginning of Witchcraft

In early human societies, witchcraft was seen as a spiritual power used to control natural elements and resolve human problems. The “witches” of that era were significant figures in tribes, valued for treating diseases, improving crops, and protecting against natural disasters.

In ancient Egypt, Babylon, and Greece, women were often considered witches if they mastered astrology, medicinal herbs, or other mysterious sciences. For example, in ancient Egypt, the goddess Isis was regarded as the master of magic. Women sometimes held high positions in society, but this depended on circumstances and events.

The Middle Ages: Oppression Against Witches

During the Middle Ages, Christian Europe witnessed a strong backlash against witches. In this period, witchcraft was seen as a pact with the devil, and women, in particular, became victims of this belief.

Notable events include the 15th-century publication of the book Malleus Maleficarum, which fueled hatred against witches. This book provided methods for identifying witches and eradicating them. Thousands of women in Europe were accused of witchcraft, burned alive, or subjected to other atrocities.

The Modern Era: A New Perspective on Witchcraft

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the Age of Reason brought about a decline in ideas opposing witchcraft. Witches became part of cultural stories and folklore, but superstition remained alive.

In modern times, especially in South Asia, superstition took on different forms. Women were often viewed as “Pirin,” spiritual healers, and practitioners of magical rituals. Social issues and ignorance have kept these practices alive even today.

Superstition and Witchcraft in Pakistan

In Pakistani society, superstition and witchcraft hold a notable influence, deeply ingrained in cultural and social dynamics. These practices often intersect with traditional beliefs, religion, and societal norms, shaping perceptions and actions across different strata of the population. Healers, spiritual leaders, and “Pirins” (female spiritual guides) have been key figures in addressing domestic, emotional, and even political issues, reflecting the widespread reliance on mystical interventions to solve personal and communal problems.

Historically, superstitions and magical practices in South Asia have roots in a mix of indigenous traditions, Islamic mysticism, and Hindu rituals. With the advent of Islam in the region, elements of Sufi mysticism were integrated into local beliefs. Spiritual leaders and saints became central figures, offering guidance, blessings, and solutions to worldly problems through divine intercession. Over time, this reverence extended to their descendants or self-proclaimed successors, creating a space for practices such as faith healing, amulet-making, and rituals aimed at warding off evil or ensuring success.

In contemporary Pakistan, these traditions persist, often serving as coping mechanisms for people facing social, emotional, or financial challenges. Many turn to spiritual leaders or “Pirs” for solace, believing in their ability to influence fate, provide relief from hardships, or grant blessings for marriage, fertility, or prosperity. While these practices are not confined to any specific gender, women are particularly involved, either as seekers or practitioners. The role of “Pirins,” or female spiritual guides, has grown, with some women carving out spaces of influence in a predominantly patriarchal society.

One significant aspect of this phenomenon is its intersection with gender dynamics. Women, often marginalized or confined within societal boundaries, find in these practices a form of agency and support. They approach spiritual leaders for guidance on domestic disputes, marital harmony, and health issues, areas where traditional medical or legal systems might fail them. On the other hand, some women adopt the role of spiritual healers themselves, earning social respect and economic independence.

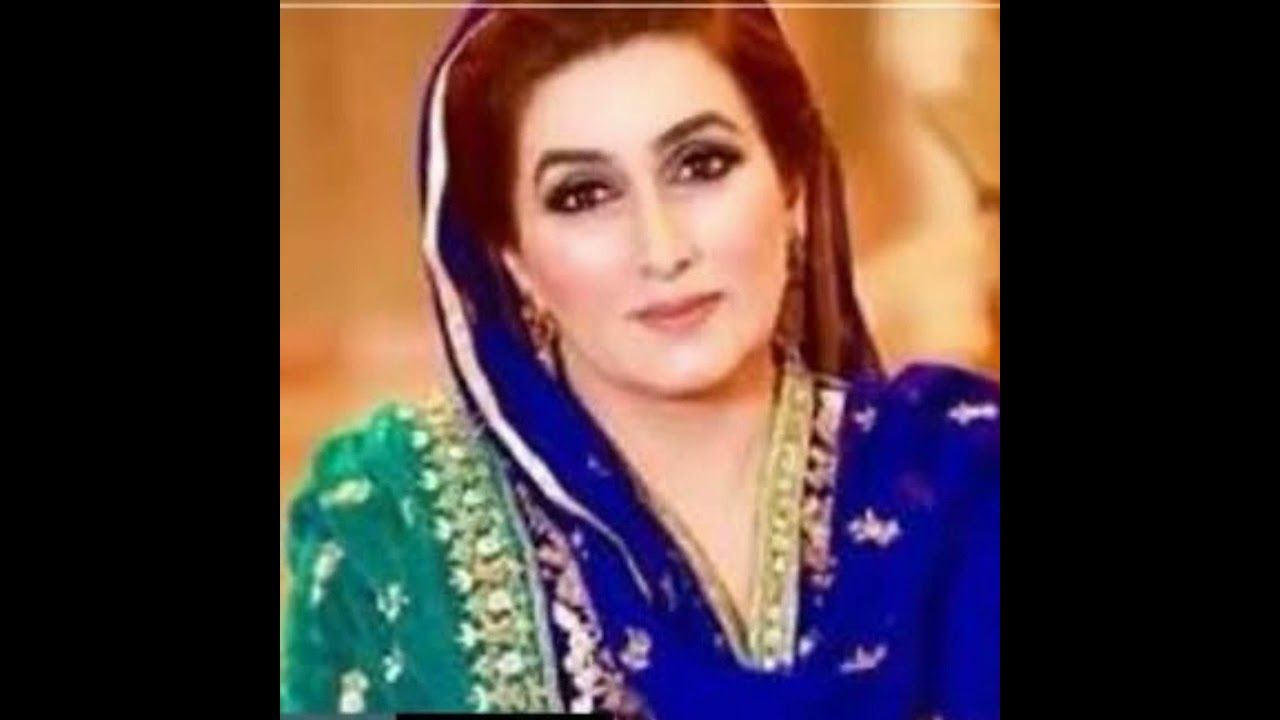

In the political sphere, superstition and spiritual practices have a more complex and controversial role. Politicians and public figures, including some of the most prominent leaders, have been associated with spiritual guides or rituals believed to influence their fortunes or strengthen their positions. The case of Bushra Bibi, popularly known as “Pinky Pirni,” illustrates this intersection vividly. As the wife of former Prime Minister Imran Khan, she has been portrayed as a figure of mystical influence, guiding her husband’s decisions and political strategies. Whether based on truth or speculation, such narratives reflect the deep-rooted belief in the supernatural within the public imagination.

Despite modernization and the availability of scientific solutions, the reliance on superstition and witchcraft persists in Pakistan, fueled by a combination of cultural traditions, socio-economic disparities, and a lack of accessible healthcare and education. Addressing these practices requires a nuanced understanding of their role in society, along with efforts to promote critical thinking, awareness, and alternative support systems. While superstition provides a sense of hope and agency to many, it also perpetuates cycles of dependence and exploitation, underscoring the need for a balanced approach to its impact on Pakistani society.

Pinky Pirni: The Tale of Today

In Pakistani politics, “Pinky Pirni” emerged as a controversial figure, her real name being Bushra Bibi, the third wife of Imran Khan, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan. She is reputed to possess expertise in spiritual practices and witchcraft, allegedly wielding significant influence over Khan’s political strategies and personal decisions.

Pinky Pirni first came into the public spotlight when Imran Khan announced his marriage to her. This union sparked widespread intrigue, as media reports suggested that Bushra Bibi was not only a spiritual guide but also a practitioner of rituals and superstitions. Some reports credited her prayers and spiritual interventions with playing a key role in Khan’s political achievements, including his ascent to power in 2018. These allegations, whether grounded in fact or speculation, captured the imagination of the Pakistani public and added a mystical dimension to Khan’s political narrative.

The relationship between a modern political leader and a spiritual figure like Pinky Pirni was both surprising and polarizing. For many, it raised questions about the influence of superstition and non-traditional beliefs in decision-making at the highest levels of government. While some viewed her as a supportive partner contributing to Khan’s vision, others criticized the reliance on spiritual practices in a country grappling with numerous socio-economic and political challenges.

Pinky Pirni’s emergence highlights the enduring interplay of tradition, superstition, and modernity in Pakistani society, where spiritual figures continue to command influence and respect in both public and private spheres. Her story underscores how deeply rooted cultural beliefs can intersect with contemporary politics, shaping perceptions and sparking debates on the role of faith and spirituality in governance.

The Impact of Witches and the Future of Superstition

The role of witches and superstitions has varied across different societies. Witches have been revered at times and subjected to severe oppression at others. Pinky Pirni’s story proves that the effects of superstition and witchcraft are still alive today, and these trends can only end through societal awareness and the promotion of education.

Conclusion

The history of witches is a fascinating and controversial aspect of human civilization. The witches of the early era were tribal leaders, but during the Middle Ages, they were considered allies of the devil. In the modern era, witchcraft became part of culture and folklore, but superstition replaced it.

In Pakistani society, figures like Pinky Pirni highlight that the influence of superstition and spiritual practices still exists. This story compels us to think that without societal development and education, it is impossible to eliminate trends like superstition and witchcraft.

To watch this article on youtube,kindly click here: